Throughout history times of accelerated change have been accompanied by cries of things “coming to an end.” Before we had solid academic research on the subject, we were told social media would be the death of community and place-based interaction. Academia has found this is not the case as digital networks are reconstructing relationships in a way that introduces values and projects in place of physical proximity. Similarly, with language, the plurality of abbreviations, memes, and character-restrictive media are often mentioned as foreshadowing the death of grammar and language. It is not, but there is a change. Consider this:

- When email emerged as a communication medium, most users were young and employed slang, vernacular and wild abbreviations. But as this form of communication was adopted by more (and older) people, the technology provided better user interfaces like Outlook and more conservative and formal styles became common.

- Before 2009, Twitter prompted users with the question, “What are you doing?” to a mostly young audience. After 2009 they prompted, “What’s going on?” This important shift changed the linguistic character (and has since defined the purpose) of the network, giving way to announcements, news, and commentary, widening the possibilities for brands to engage with customers like never before.

The problem with generalizing a ‘digital dialect’ is the same problem we encounter when we try to generalize digital. Networks come together for different reasons. The linguistic character of LinkedIn is different than the linguistic character of Twitter and Snapchat. Realize that consumers invent, out of necessity or creativity, terms and phrases used to describe a brand’s idea and/or products. Kids will always make up new words, some of which become a part of the pop culture. “Bae,” “Turnt,” “Flawsome,” are three examples. The question brands are faced with is: Do we maintain proper linguistic convention and adhere to the brand’s style manual, or do we give in to channel-native dialect?

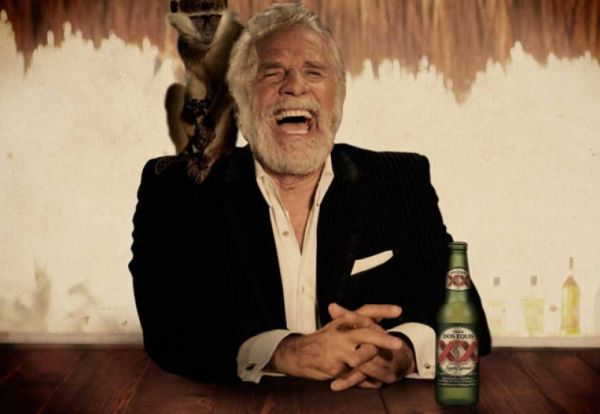

“Using channel-native language,” as Forbes’ Jayson DeMers suggests, “could be considered a form of meme-vertising.” Meme advertising is more than just a creative phrase on an image, it is an interpretation of a key cultural moment as a strategic and humorous message. Both channel-native language and meme-vertising is a risk. Dos Equis’ has famously used this technique to extend their ‘most interesting man in the world’ campaign well beyond television and they do it brilliantly.

Conversely a web search on social media blunders will return a near-infinite amount of brands which imagined themselves clever by trying to leverage trendy keywords. Remember that nobody owns these kinds of terms/phrases, and while mistakes on the social web are regularly forgiven and even more easily forgotten, the eye-blink it takes for new words to appear can also be enough time to use them in ways that damage the brand idea in consumers.

Here are three questions to which brands should quickly have an answer:

- What is the brand purpose? By and large, we’re seeing portfolios of brands increasingly consolidated. In terms of customer engagement, this offers a better opportunity for the brand story to come to life in a stronger, unified way. An architecture change of this magnitude must include a new definition of purpose. For other brands, review your existing purpose. To engage customers with any hope of authenticity, purpose must be as constant as the northern star. With a solid purpose, the words become secondary to the intent allowing greater fluidity in how the brand engages across channels.

- Is the brand authentic (true to its purpose)? The lure of channel-native vocabulary can be very tempting. The goal of customer engagement on the social web is to have the brand welcomed as ‘one of us.’ But each network has different, changing, and undocumented conventions on ‘how much is too much,’ making it impossible to generalize. At the same time, the very nature of a shorter conversation is brevity. In B2B especially, there is a delicate balance between connecting at a human level and simplifying the language so much that it comes at the expense of the brand’s position and differentiation.

- How is the brand contributing value? The cost of engagement is time. Channel-native language and meme-vertising often brings value in the form of humor. Other engagements might bring knowledge, ideas, resources, but the line between promoting (which is likely a response) and engaging (which demonstrates understanding) is not always easy to see.

Brands can easily find themselves wrapped up in the dynamo of ever changing terms and networks when they compromise on purpose. Every brand will need to define their rules of engagement, and those rules, simply by the dynamic nature of language itself, will evolve on a daily basis.

The Blake Project Can Help: Accelerate Brand Growth Through Powerful Emotional Connections

Branding Strategy Insider is a service of The Blake Project: A strategic brand consultancy specializing in Brand Research, Brand Strategy, Brand Licensing and Brand Education

FREE Publications And Resources For Marketers

No comments:

Post a Comment